What is going on in your brain while doing mindfulness?

Mindfulness helps us focus, become more aware, relax, and calm ourselves down. In the last 10 years, imaging and other studies have started being able to show objectively which areas of the brain are affected by mindfulness and meditation. In addition to giving us a more detailed look into what happens during mindfulness and meditation, this kind of science is a good motivator to practice mindfulness. Just like physical exercise makes you stronger, mindfulness makes your brain work better. And now we’re starting to have some rigorous scientific evidence to prove it.

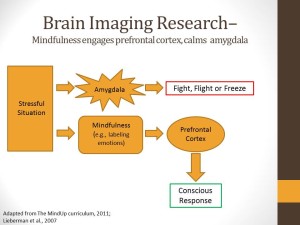

Let’s start with two important structures in the brain:

- the amygdala – a pair of almond-shaped structures deep within the brain’s limbic system that acts as the brain’s ‘security guard’ by triggering an automatic reflexive response of “fight, flight or freeze” when it perceives a threat and

- the prefrontal cortex – the learning, reasoning and thinking center of the brain, located behind the forehead.

Sensory input perceived by the amygdala as pleasurable or neutral is allowed to proceed to the prefrontal cortex for analysis and response. On the other hand, if the sensory input is perceived as threatening, the amygdala blocks analysis by the prefrontal cortex so that the body can immediately react to this ‘emergency’. This is fine if a bear is chasing you or a heavy object is about to drop on you. In those cases, a quick, automatic response could be the difference between life and death.

The problem is the amygdala doesn’t always make a distinction between actual dangers and perceived threats. For example, we sometimes freeze in stressful situations, such as a test or having to speak in public, or we might lash out in words or even physically when angry or frustrated.

Take a look at the diagram below. When stressful situations trigger our amygdala we are literally acting before we are able to think rationally. If at that point we can notice this reaction occurring, (that is, the amygdala being triggered) then say to ourselves, “I’m feeling angry now”, we can allow information to flow again to the prefrontal cortex and make a rational response. Noticing what is happening is a basic mindfulness technique. Simple noticing and labeling of the experience as well as other mindfulness techniques such as counting to 10, doing some mindful breathing, mindful listening, or mindful seeing can often be enough to create the space needed for rational thought to kick in once again.

This discussion and the diagram to the right is adapted from The MindUP Curriculum: Grades 3-5: Brain-Focused Strategies for Learning-and Living, 2011, Scholastic Press. Click on the diagram to view it larger.

This discussion and the diagram to the right is adapted from The MindUP Curriculum: Grades 3-5: Brain-Focused Strategies for Learning-and Living, 2011, Scholastic Press. Click on the diagram to view it larger.

Explaining brain science to kids

To make this more understandable to young children, I read them the book, When Sophie Gets Angry — Really, Really Angry . . .by Molly Bang. This picture book tells the story of a little girl who gets really angry after being triggered by her sister taking her stuffed gorilla, complete with shouting, smashing and running (all classic amygdala reactions to threat). She cools down by listening to sounds in nature, climbing a tree, and feeling the breeze (mindfulness techniques). After that she is back together again and can return home to her family, calm and rational once more (her prefrontal cortex is working again!). The children can definitely relate to Sophie’s experience and really enjoy the story.

Help you child notice when he or she has been triggered by anger, frustration, stress, or other situations. If they like using the brain terminology you can refer to the amygdala and the prefrontal cortex. Noticing it in yourself can be a way to do it in a less threatening manner as in, “Wow, I think my amygdala really kicked in there when I started yelling, were you feeling that too?” Remind your child to use one of the mindfulness techniques to help them cool off. After that you can start discussing rational ‘solutions’ to whatever caused the original problem, this time with the rational part of the brain, the prefrontal cortex, operating more normally.